Avast there! Duffus: County’s Blackbeard heritage being stolen

Published 4:36 pm Saturday, February 1, 2014

KEVIN DUFFUS | CONTRIBUTED IMAGE

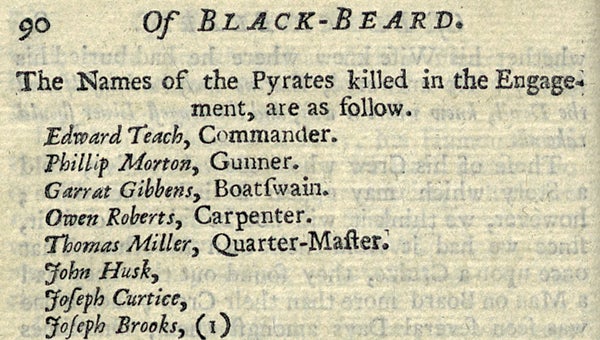

DEAD OR ALIVE? This list shows the names of members of Blackbeard’s crew purportedly killed off Ocracoke Island or hanged in Virginia. Historian Kevin Duffus believes the list is not accurate.

By MIKE VOSS

Washington Daily News

Beaufort County’s claim to the pirate Blackbeard is being stolen at worst and misrepresented at best, according to Kevin Duffus, author of several books about Blackbeard and other aspects of North Carolina coastal history.

Duffus is slated to discuss Blackbeard’s legacy during a multi-media presentation — “Blackbeard’s Black Pirates” Their Origins, Their Identities, and Their Fates” — he will give at the Turnage Theater at 2 p.m. Feb. 16. The lecture is sponsored by Friends of the Brown Library and the N.C. Humanities Council. The event is free and open to the public.

Duffus believes some media outlets and other researchers of Blackbeard’s history are not telling the true story of Blackbeard, either on purpose or out of ignorance because of poor research discipline. Duffus said his lecture provides detailed information to support his claims.

“There seems to be a conscious effort on the part of some historians to blur the lines between piracy and slave trade,” he said. “The point I’m trying to make is that the blacks aboard pirate ships were slaves.”

The lecture

“The theme of the presentation is about how blacks have been portrayed aboard pirate ships. It’s of particular interest to Bath and North Carolina and the Queen Anne’s Revenge (a Blackbeard vessel) in particular because when the Queen Anne’s Revenge was wrecked in Beaufort Inlet, one of the pirates that Blackbeard abandoned and left behind ended up in a court in Charleston (S.C.) later that year. He testified under oath that Blackbeard departed Beaufort Inlet, after wrecking the Queen Anne’s revenge, with 60 blacks and 40 whites aboard what became known as the sloop Adventure. That sloop sailed around Cape Lookout, into Ocracoke Inlet and up to Bath ‘ arrived at Bath around the first of July 1718.”

Duffus said pirate historians tout this information as an example of how racially diverse pirate crews were — that they were multicultural, transnational and all-inclusive.

“But what these pirate historians have failed to note, either because they didn’t carry their research any further or they did — and they are aware of the truth — but six months later when Blackbeard was killed at Ocracoke Island, he had aboard his ship just six blacks. And that leaves 54 other blacks, or Africans, somewhere,” Duffus said. “But some of these pirate historians have suggested that when arrived at Bath they were each given a flintlock pistol and their freedom and 40 acres of land. But in my research in the deeds of Beaufort County, I have discovered, for the first time in this county’s history, going back to the late 1600s, that within two weeks of Blackbeard’s arrival in the summer of 1718, large pieces of property were being sold for the price of slaves.”

Duffus said one man bought a plantation for the price of two slaves whose names were listed in the deeds as Pamptico and Pungo. Pamlico is considered a variation of Pamptico.

Duffus said bringing the blacks to Bath made sense because people were needed to work on the plantations in that area. Duffus also believes those blacks with surnames like Brooks and Jackson have descendants in Beaufort County today.

“There are other indications that other pieces of property were sold. Everywhere in the records, I’ve been able to single out, identify and, in some cases, name slaves who were part of the 60 blacks who supposedly were equals aboard Blackbeard’s ship, who have all been referred to as slaves in the records,” Duffus said. “The fact that I cannot locate 40 men suggests to me that they actually were absorbed, assimilated into the plantation society of the Pamlico by those families who were associated with Blackbeard’s crewmembers.”

Duffus contends the great majority of those 60 blacks became slaves on those plantations.

“This is an aspect of pirate history, traditional history and Beaufort County history that no one has been willing to tell.”

Leesa Jones, who leads tours in Washington that focus on the history of local blacks, is excited about Duffus’ findings.

“What his research as done as put some meat on the skeletons of stories I heard growing up. I would hear the older people sitting around the porch talking about what they referred to at the point as black pillars. I think that the translation from pirate to pillar I can easily see how that happened because some people drop letters out of words. They were often referred to as the black pillars that came on pirate ships,” Jones said. “They would talk about how they knew someone who was related to and they would call a particular name. As I kid hearing these stories, they meant absolutely nothing — until I started doing research and I started to find very fine threads that somehow started to relate to other things.”

Jones said when she began reviewing Duffus’ research, she got a better picture of the history of the area.

“I realized that some of the stories I heard growing up — from my grandparents and great-grandparents — may have had a great deal of validity to them. … Part of what I do is try to track down these stories and make sure there is truth in them. … The stories about the black pillars now makes sense,” Jones said.

Jones said Duffus’ research tracks with her research concerning black families that have roots in the Bath area.

Heritage stolen

Duffus believes Beaufort County’s heritage has been stolen, or buried, by entities misrepresenting the county’s Blackbeard heritage.

“Some of these organizations and Bristol, England, are trying to claim Blackbeard for themselves at the cost of Beaufort County and Beaufort County’s history. It’s very clear that the majority of Blackbeard’s white crewmembers were the sons of plantation owners on the Pamlico. Now, it’s very clear that the 60 blacks who were aboard the Queen Anne’s Revenge were slaves who were brought into Bath Creek and dispersed,” Duffus said. “Ultimately, the point I’m trying to make with this program is that there are, almost certainly, people living in Beaufort County who are not just descendants of the white pirates but also descendants of the blacks … the 60 slaves who were brought to North Carolina by the Queen Anne’s revenge.”

Duffus hopes the lecture and his research will culminate in an effort to develop a genealogical and oral history project to locate stories, oral tradition and written evidence there are families that are descendants of the white pirates and black slaves.

See the Feb. 9 edition of the Washington Daily News for information about a black man named Caesar who was part of Blackbeard’s crew. Some reports claim Caesar was executed by hanging, but evidence suggests he was not done in by the noose.