The night they drove old Dixie down

Published 7:53 pm Wednesday, August 22, 2018

For good or for ill, the toppling of Silent Sam on the campus of UNC-Chapel Hill on Monday will be a day long remembered at the university.

The pulling down of the statue, and the powerful reactions that followed in its aftermath, reveal that North Carolina is very much a divided society when it comes to the issue of Confederate monuments. While some applauded the crowd for its actions, others suggested that those present should face criminal charges and be expelled from the university.

On the one hand, you have those who see monuments such as Silent Sam as reminders of a hateful and discriminatory past; towering monuments erected during the height of Jim Crow segregation to remind black people of their place.

On the other hand, some North Carolinians view the destruction of the statue as an insult to the memory of the Confederate dead, and an attempt to rewrite history. Even more odious to this group is the manner in which the statue was vandalized and destroyed.

There are two sides to every story.

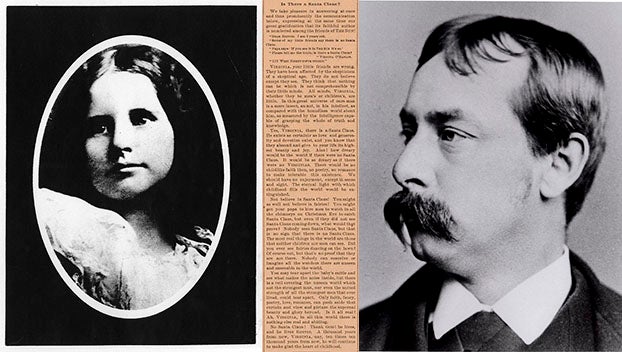

During the speech given during the dedication of Silent Sam, Confederate veteran Julian Carr, amidst poetic imagery of the beauty and splendor of the South and the university, said this of the Confederate soldier: “their courage and steadfastness saved the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the South” — When “the bottom rail was on top” all over the Southern states, and to-day, as a consequence the purest strain of the Anglo Saxon is to be found in the 13 Southern States — Praise God.”

In the same speech, he dips into an allegory on how, upon returning from Appomattox, he “horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern Lady.”

While Carr has been painted as a villain in the saga of Silent Sam, it is also important to remember he was a product of his time. According to a 2017 op-ed in the News & Observer written by UNC history professor Peter A. Coclanis, Carr was also a leading industrialist of his day, a generous contributor to overseas missions, a strong supporter of women’s suffrage and a patron of John Merrick, one of the founders of the North Carolina Mutual Life insurance Company, one of the state’s foremost black-owned businesses.

A wise man once said that the past is a foreign country, and the people who live there do not share the same morals and sensibilities that we do in the present day. We can only try to understand them, realizing that our knowledge is obscured by our own biases.

Were there some in the crowd at the dedication in 1913 who believed that the statue was a symbol of Anglo Saxon dominion over the United States? Probably. Were there others in the audience who mourned lost husbands, fathers and brothers who died in service to the Confederacy? Almost certainly.

Both sides of the debate over North Carolina’s confederate monuments have valid points. The best we can do is try to see where the other side is coming from and work towards a solution that preserves history while acknowledging its dark side.