University researchers to digitize Beaufort County slave deeds, local volunteers welcome

Published 6:08 pm Monday, August 5, 2019

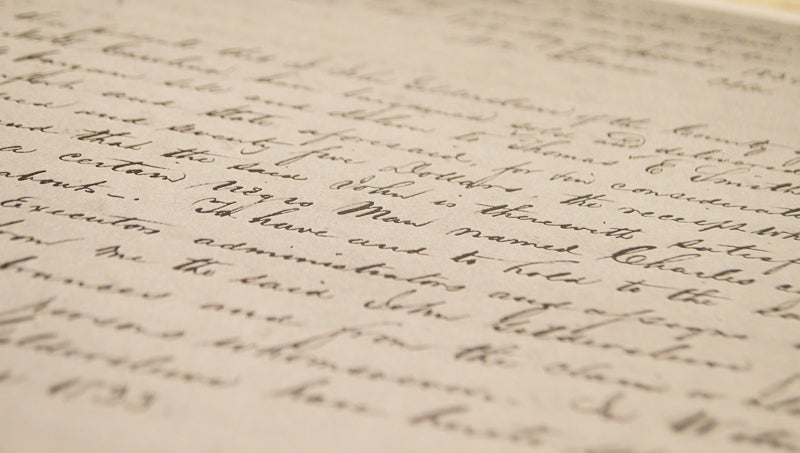

- COMMON PROPERTY: This bill of sale from 1834 records the sale of “a certain negro man named Charles” from John Gildersleeve, of Craven County, to Thomas E. Smith, of Beaufort County. Charles, who was around 50 years of age, was sold for the price of $175. Researchers with the University of North Carolina–Greensboro-led People Not Property project will seek out and digitize thousands of historical records like these in 26 counties throughout the state. (Matt Debnam/Daily News)

Land deeds, titles to cars and boats, bills of sale for livestock — these common documents change hands daily in North Carolina, each signifying ownership over a particular piece property. In historical records at the Beaufort County Register of Deeds, however, these same types of documents show a darker trade: the buying and selling of enslaved people.

These so-called “slave deeds” are the focus of a new project in the works at University of North Carolina–Greensboro called People Not Property — Slave Deeds of North Carolina.

On Thursday, researchers leading the project are slated to visit Beaufort County, with scheduled stops at the Washington Waterfront Underground Railroad Museum and the Beaufort County Register of Deeds. From 5 to 5:45 p.m., the public is invited to an information session at Brown Library to learn more about the project and how to get involved. The featured speaker at the event, North Carolina A&T Professor Dr. Arwin Smallwood, will speak about the African-American history of the region.

“With very few exceptions, due to things like flood and fire, most counties do have all their records going back to the founding of the county,” said People Not Property coordinator Dr. Claire Heckel. “… The challenging part is going through page by page, because the slave deeds are not separate from, say, land deeds or livestock deeds. What our volunteers and staff are doing currently is reading through thousands of pages of deeds to identify the ones that actually are pertinent to enslaved people.”

The People Not Property project will add to many resources already available through UNC–Greensboro’s Digital Library on American Slavery. Included in this collection are thousands of court documents, runaway slave advertisements from newspapers and information about the transatlantic slave trade.

Now, thanks to a three-year, $294,603 grant from the National Historic Public Records Commission, researchers and community volunteers from 26 North Carolina counties have undertaken the task of finding and digitizing nearly 10,000 slave deeds from throughout the state.

The end result of the research will be a more complete picture of the slave trade in North Carolina, as well as a searchable resource for genealogists and those interested in exploring family histories at a time when few enslaved people left behind written records.

“These are some of the only written documents that might provide things like names and ages for enslaved people,” Heckel said. “So I think through a combination of family oral history, or family Bibles or family stories with first names, or perhaps having a last name that gets you back to a particular slaveholder or plantation, I think these documents are essential to genealogists.”

To learn more about the Digital Library on American Slavery and the People Not Property project, visit library.uncg.edu/slavery.