Getting to know who you are and why you are here: The life story of Betty Randolph

Published 3:00 pm Saturday, April 1, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Clark Curtis

For the Washington Daily News

Editors Note: During Women’s History Month, Clark Curtis will be taking a look at some of the women, past and present, whose stories and lives have contributed in some way to the deep and rich history of Washington.

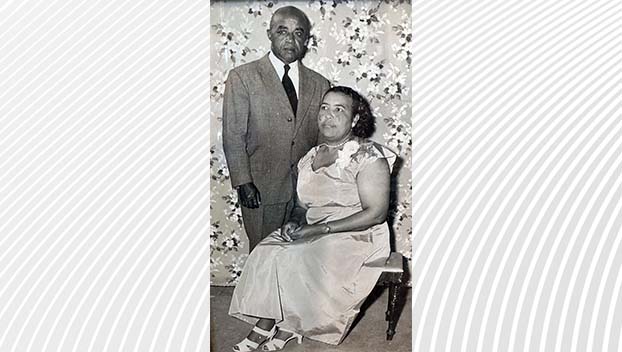

Betty Jean Barr Randolph was born in 1942 in the small rural town of Greelyville, South Carolina. Her parents were both educators. Her father, Eason Ralphord Barr Jr., was a principal for 33 years at the local school. Her mother, Annie Richburg Barr, was a third grade teacher. As a highly respected educator in the community she was asked to move to a formally all white school following integration to teach kindergarten children. It would have been the first time a lot of those children had ever seen a Black teacher and it proved to be a wonderful experience for all.

For Randolph, growing up in the small community of Greelyville was no different than growing up in any small southern town in those days. “The school I attended was all Black,” said Randolph. “The people who lived on the street were I lived were all Black . The other children I played with in the afternoon after school and on Saturdays were all black.” But, there was no hiding the fact that she was also growing up in a time of segregation when people were treated differently based on the color of their skin. Randolph recalled going to the local department store with her mother and seeing for the first time water fountains labeled colored and white.” I asked my mother what color was the water coming out of the colored fountain” said Randolph. “She replied, “the same that is coming out of the white.” That really was the first time I knew I was colored and things were different.”

In the summers, Randolph would often travel by train to visit her grandmother and aunt in New York City. On her first visit she immediately saw that things were much different there than in the South Carolina Low Country. “My aunt lived in a single family home on a street where both White and Black people lived. As a child I can remember being very puzzled by it all.”

One summer, when she was ten or so, her father came to pick her up in New York and drove her back home. On that trip she would experience one of the first hard lessons in life. They stopped briefly at a roadside store along Highway 301 to go to the bathroom. “When we pulled up I remember my dad saying, “can you hold your trickle for just a bit longer?” I said “yes” but I asked why. He pointed out that the bathrooms were marked “white” and “colored” and that meant I could not go into the white one no matter what and he chose that I not have to go into the “colored” bathroom.” She of course, asked if the toilet in the white bathroom was different than the one in the colored. He replied, “No. I just don’t want you to have to feel that this is how you are going to have to live all of your life, because it is so ridiculous.”

Randolph would often ride her American Flyer bike to the post office to get the mail and then walk over to the five-and-dime to get a new funny book that came out each Wednesday. It was on one of those Wednesday’s that she encountered the “N” word for the first time. “I was walking my bike along the street and a little white boy sitting in his parents car yelled out to me, “N#!#er, what are you doing walking on the sidewalk?.” When she got home she shared what had happened with her mother and grandmother. “You know what,” they said, “he probably can’t even spell it and doesn’t even know what it means.”

At a very young age, Randolph would also see for the first time, a chain gang working in the school yard directly across the street from her house. “I saw these Black men in striped clothes and what appeared to be chains around their ankles. When we sat down for dinner that night I asked my father about it. My mother immediately stretched her long “Richburg” leg under the table and kicked me, which meant for me to shut up. I know now how painful it was for my father to try and explain what I had just seen that afternoon and what we experienced on our long drive home from New York.”

Randolph also credits her childhood teachers for trying to expose their students to as much “Blackness” as possible while growing up. And what seemed then to be only field trips, proved to be life lessons learned. “We would read and sing Black hymns and discuss what they meant,” said Randolph. “We went to Charleston one time to visit the former slave markets and learn of how our ancestors were bought and sold. These were the learning experiences that clearly pointed out to a young person that being Black was a little different than being White.”

Many of the students who attended high school with Randolph were children of the local share croppers who worked the land growing tobacco and cotton. “When it came time for for the crops to be harvested those children were no where to be found in school,” said Randolph. “They would pick the tobacco during the day and then stoke the fires all night in the barns as they dried it. Often times they would not be back in school until late October. There was no way they could keep up with the rest of the students, and when they got old enough they would drop out and leave the area.”

Randolph would go on to graduate from high school in 1959 and was fortunate enough to be able to attend North Carolina Agriculture and Technology (A&T) University in Greensboro, NC. “My fathers’ training was in the field of agriculture and he told me under no certain terms would I go there to enroll in agriculture, so I chose home economics. Training that would allow me to go on and work in rural Beaufort and Wayne counties.”

As a freshman in 1960, Randolph was in Greensboro when four young Black students from the University started a sit-in at the segregated Woolworths’ lunch counter and refused to leave after being denied service and were beaten and arrested. “I remember calling my father to let him know what was happening” said Randolph. “All he said was, “I would rather you not participate in any protest marches, but I know you will, so be careful.”

There were many protests marches following the first incident. Randolph participated in one of those which was led by the president of the college, Dr. Samuel D. Proctor. She recalled seeing another incident when some protestors were being served at the counter. “All of the sudden the man who was serving them, picked up their plates and threw them on the floor. I told my father what happened and his only response was, “fine, that’s one less plate that he can’t serve another meal on. He will just have to go out and buy a new one.” Randolph added, “those college students wore out the White people in Greensboro.”

Randolph would go to to graduate from NC A&T in 1963, and with diploma in hand set out for her first of many jobs in Beaufort County.

In our continuing story about Randolph, I will share more about her remarkable life and career in Washington and its lasting impact.