Getting to know who you are and why you are here: The life story of Betty Randolph

Published 6:33 am Wednesday, April 5, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Clark Curtis

For the Washington Daily News

Editors Note: During Women’s History Month, Clark Curtis has taken a look at some of the women, past and present, whose stories and lives have contributed in some way to the deep and rich history of Washington. This is part two of his story about Betty Randolph and her contributions and life here in Washington.

Following her graduation from North Carolina A & T in the Fall of 1963, Betty Randolph would take her first job as a home economist extension agent with the Beaufort County Agriculture Extension office located on Fifth Street. A building that had actually been built by Black female extension workers. “I was privileged to be able to work with Mr. Chester Bright and his secretary, in what was then an all Black office, said Randolph. “I was able to work with the local women’s clubs and the local 4-H program. I also went on to become a community development agent where I motivated people to build their own homes and to get into the farming business and establish their own poultry farms. I simply loved all of the people I worked with and had such a wonderful experience while I was there.”

In the Fall of that same year Randolph was given the opportunity to transfer to the Agriculture Extension office in Goldsboro. An opportunity that she considered to be a true blessing. “I was young and full of energy,” said Randolph. “The lifestyle was just different there. The complexity of the programs that we were able to initiate was on a much grander scale. There were more farms and so many more employment opportunities. It was a great learning experience and a joy to be there.”

In 1969 Randolph was given the opportunity to transfer to the Agriculture Extension office in Alameda County, California, across the bay from San Francisco, where she became a home adviser. “What an experience that was,” said Randolph. “The needs of the people were so different. Instead of working with tobacco and cotton farmers, you were working with those who farmed fruit trees and vegetables. There was such a diversity of people and occupations, but it all still fell under the umbrella of the USDA.”

Randolph was also amused by the fact that everyone in the office wanted to know more about her experiences in North Carolina. “I was like a crossword puzzle for them as they had a need to know more,” she said with a grin. “It was such a wonderful experience there. You can imagine what this must have been like for a brown little girl who grew up in Greelyville, South Carolina, went to NC A & T, and worked in two different counties in North Carolina before transferring to California.”

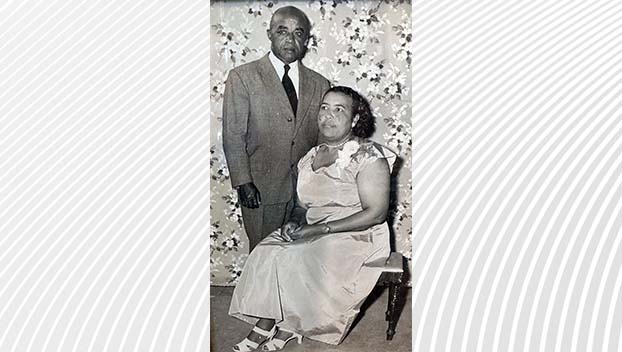

It was also during this same time that a young man she had met from Beaufort County had become much more serious in his long distance overtures. So much so that he asked her to be his wife. On December 5, 1970 she would wed Louis Randolph, and return to Washington where she has remained ever since.

Betty and Louis would go on to touch countless lives in Washington and the state of North Carolina for many years. Randolph worked at Beaufort County Community College for 13 years in early childhood preparedness education. “This gave students a chance to obtain a working background so they could open a daycare or work in a daycare,” said Randolph. “It also gave them the opportunity to work in the public schools pre-K programs. During this time we were also blessed with the birth of our daughter Naomi Ann Randolph, and Louis starting his own funeral home business.

After 13 years Randolph left her position at the community college to work at Martin County Community Action. There she worked with and assisted those in need of getting high school diplomas and tutored others on how to fill out job applications and many other life skills. She was also asked to serve on the Beaufort County Developmental Center board of directors, where she worked with and developed programs for intellectually challenged adults. “When the O’Berry facility in Goldsboro closed, these individual were in need of some structure and opportunities,” said Randolph. “Fortunately we were able to take them in and offer the care and training that they so desperately needed.” Randolph would go on to be named director of the board.

With her service to the community never wavering, Randolph would also serve as chair of the Beaufort County School board and become a member of the Beaufort County Community College board of trustees. “This was a very intense but rewarding time in my life and my husbands’ as well.”

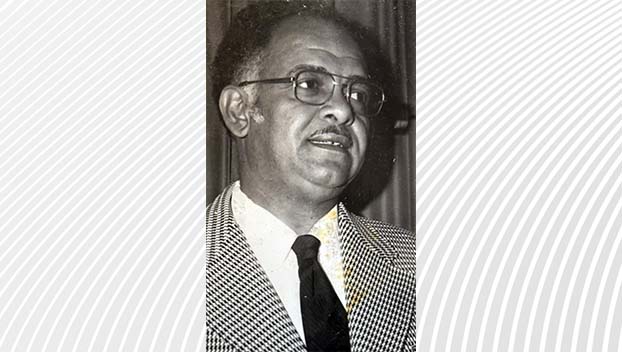

In addition to running his funeral home, Louis Randolph served as a trustee at his alma mater, Elizabeth City State University. From there he would become a member of the UNC Board of Governors where he served for 19 years. “This was at a time when schools were beginning to integrate and Black students had more options available to them,” said Randolph. “He would personally guide and prepare these students so they would become highly respected and desirable to the universities and colleges that were now opening their doors to Black students. It was so broadening for him as he had so much knowledge about African American students.”

Louis became the first Black to serve on the Washington City Council. He also ran for mayor, losing by only 52 votes. “He carried a lot of love and concern for this community on his shoulders,” said Randolph.

As Randolph also shared, her husband became known as a facilitator for bridging the racial divide in Washington. “There was an incident of some sort at the local Hardee’s between Black and White kids,” said Randolph. “The Black kids came to Louis for guidance and of course he could not say no and stepped in to ease the tension. Following that incident Louis let it be known to the African American community exactly who he was, that he knew he was black and that he would never forget that. And at the same time, the White community recognized that if some bridges were going to be built, mended, or structured to be welcoming, that he would be someone they would listen to. I’m so proud to say that I was his wife.”

When Louis passed Betty shared that she had already made some decisions that might be considered a bit controversial. “I decided that he would be buried in Oakdale, not Cedar Hill,” said Randolph. “As the first black to be buried there, I wanted him to awake on his judgement day and say, “Dang, look where Betty put me!” I meant nothing disparaging about the decision, nor did I feel we were better than others. I wanted to feel that I gave him in death what he had earned for himself in life. That he could integrate anything and be accepted. And what a better way to do that than on the day he was laid to rest.”

Following the death of Luis, Randolph would go on to serve as the director of the funeral home. She was bestowed an honor that she cherishes until this day. She was asked by city leaders, and then mayor Ford Brothers, to accompany the group that was headed to Florida and deliver the presentation as to why Washington should be selected as an All America City. “I remember going to the cemetery and telling Louis the news,” said Randolph with a wavering voice and a tear in her eye. “I said “Louis can you believe I’m going to be delivering the address at the All American City conference?” I know I heard him reply, “Dang I do Betty. Go for it, girl!””

Randolph said we all looked like a million bucks that day and were totally beside ourselves when they announced we had won.. “We were all decked out in our navy and white attire,” said Randolph. “I don’t know why they chose me, but those were moments that you realize it is okay to live here. That we are going to define this community, we are going to do what small town America does well when the citizens, instead of standing and looking at each other across the line, come to the line, and extend themselves to be one.”

As Randolph nears her 81st birthday, she paused for one additional reflection. “I can say that I have seen the world on both sides,” said Randolph. “I know what it is to grow up in a South Carolina Community where if you were Black you were human but you may not have had the same experiences as others. You had parents who were dutiful in making sure that whatever was the blueprint in their days did not get erased, but was enhanced and enlarged for you to move forward and still be a citizen and a human being. And no matter what, know how to be thankful, appreciative, to doubt, but at the same time always have hope. What a blessing it is to have been able to figure out who you are and why you are here.”