Local women recalls acquaintance with teen’s murderer

Published 7:51 pm Thursday, March 5, 2015

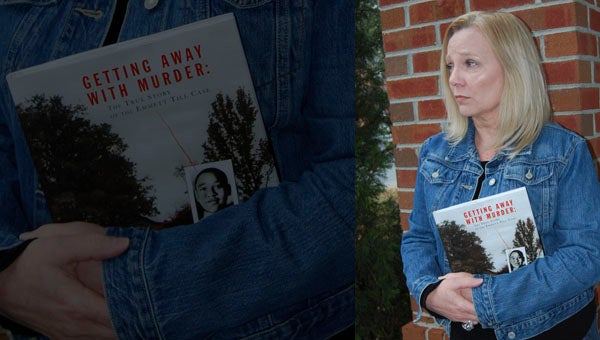

KEVIN SCOTT CUTLER | DAILY NEWS

PAINFUL MEMORIES: Clutching a book written about the murder of young Emmett Till, Melanie Gambill recalls her acquaintance with a man who later bragged about killing the African American teenager in 1955.

“I couldn’t believe I had done business with a man who killed a child,” said Melanie Gambill, her eyes filling with tears. “I never knew.”

Gambill, a former Washington resident and business owner who now lives in Greenville, was reading through Facebook posts last week when she saw a notice about the Turnage Theater’s upcoming documentary theatre production, “Dar He, The Story of Emmett Till.”

The notice brought back painful memories for Gambill, who unknowingly associated with one of Till’s killers in the early 1980s.

At that time, Gambill was living in her home state of Mississippi, residing on the grounds of Parchman Farm/Mississippi State Penitentiary; her husband at the time was a correctional officer and her father was a lieutenant at the prison.

There wasn’t much to do in the rural area, so Parchman employees and their wives often drove to nearby Ruleville where they frequented a small local establishment, Gambill recalled.

“Most of the people who lived at Parchman went to Bryant’s Country Store,” she said. “The store sold Cokes in glass bottles and they sold deli meats … my husband and I would go in there. It was just a little hangout.”

What made the store memorable was its owner, a loud, obnoxious man Gambill knew only as Mr. Bryant.

“One night we were in there we could hear him going on and on about how he wouldn’t hesitate to shoot somebody,” she said, adding that he was particularly vocal about his hatred for black people. “And a good half of his customers were African Americans! He was kind of mouthy like that. But I did not have a clue who he was.”

Fast forward a few years to 1998. Gambill, now divorced, was living in Harlingen, Texas.

“One day, I was watching Oprah Winfrey, and Emmett Till’s mother was on the show,” Gambill recalled. “Being from Mississippi, I had heard of the case. Oprah asked Mrs. Till a question about the two men who had killed her son.”

Gambill listened, stunned, as the murdered youth’s mother talked about a man named Bryant. A sick feeling washed over her; a call to her ex-husband confirmed that the obnoxious storeowner Gambill knew in Ruleville was the same man being discussed on television.

Till was an African American youth who, in the summer of 1955, left his Chicago home to travel south to visit relatives in the small town of Money, located in the Mississippi Delta region. He had turned 14 years old just a month before his murder, a crime that proved to be a pivotal event in the Civil Rights movement.

Till’s Mississippi vacation took a turn for the worst when he was accused of flirting with a white woman, the wife of a man named Roy Bryant, owner of a local store. Versions of the altercation are at odds; Mrs. Bryant claimed the young man whistled at her, grabbed her hand and talked provocatively. Eyewitnesses, including Till’s cousin and an anonymous source who was also in the store at the time, were still adamant decades later in their denials that Till acted inappropriately toward the woman. In fact, it was known that Till, who had a pronounced speech impediment when he was nervous, frequently whistled quietly to himself to overcome his propensity to stutter.

Regardless, Mrs. Bryant told her husband her version and, angered, he enlisted the help of his half-brother, J.W. Milam. On the night of Aug. 28, 1955, they kidnapped Till from the home of his great-uncle.

The teenager was never seen alive again.

For hours he was severely beaten to the point that was one of his eyes was dislodged from its socket. His tormentors then shot him through the head, weighted his body down with a 70-pound cotton gin fan and tossed him into the Tallahatchie River. Three days later his remains were found.

His distraught mother had his body returned to Chicago, where she demanded that the mutilated corpse be displayed in an open casket so the world could see what had been done to her young son.

Bryant and Milam were arrested, but they claimed that while they had indeed kidnapped the teenager, they had later set him free. What happened after that, they insisted, had nothing to do with them.

After a five-day trial, the accused murderers were acquitted. But their arrogance over literally getting away with murder did them in. Protected against double jeopardy, meaning they couldn’t be tried again for the same crime, Bryant and Milam bragged in an interview with “Look” magazine in 1956 that they had, in fact, killed the young man.

And while Mississippi’s legal system failed Till, the court of public opinion was a different matter. Even their white friends and supporters, disgusted by their admission of guilt, turned against Bryant and Milam. Each lost once prosperous businesses to bankruptcy and both later left Mississippi in an attempt to start new lives elsewhere.

In Bryant’s case, he eventually returned to Mississippi where he opened his Ruleville store. And that is where Gambill happened to make his acquaintance.

Gambill said she plans to be in the Turnage audience March 12, and she intends to bring along her daughter Emily Holbrook, who at 14 is the same age as Till was when he was murdered.

“I want her to see what hate does to people,” she said.