Preserving history the focus of alumni clubs, reunions

Published 6:10 pm Thursday, May 11, 2017

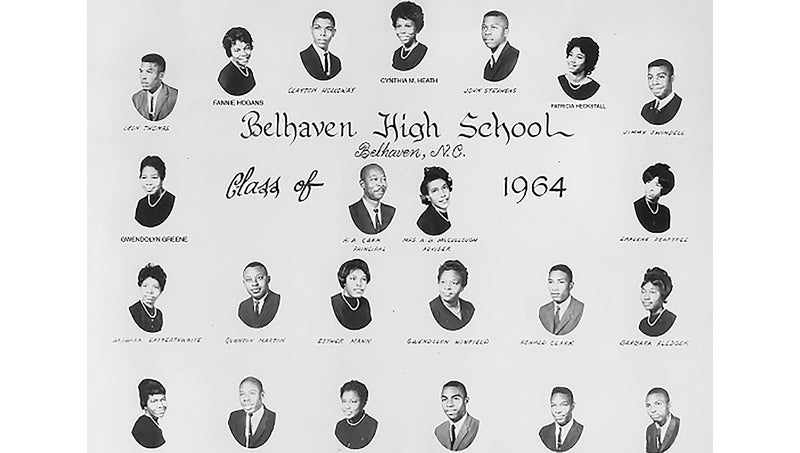

- HISTORY: The 1964 graduating class of the all-black Belhaven High School, one of several black high schools that continues to hold reunions for alumni as a way to remember and recognize the contributions of black graduates, educators and administrators to education before and after desegregation. (Belhaven High School Alumni)

BELHAVEN — Alumni of a high school once designated for black students only will gather today to celebrate past and present successes, lifelong schoolmate relationships and to ponder the future of education for all students living in rural North Carolina, especially minority students living in eastern Beaufort County.

For graduates of the former Belhaven High School, it’s a 55-year-old annual tradition that has its roots in segregation and raising funds to support then-intentionally underfunded, all-black public schools. Though the schools are long gone, their graduates continue to meet.

Three miles down the road, the former Beaufort County High School alumni group of Pantego gathers annually the first weekend in May, followed by the Belhaven High School alumni the second weekend. For nearly 50 years, alumni of the former O.A. Peay School and Hyde County Training School of Swan Quarter gathered two weeks later, on Memorial Day weekend, though in recent years their activities have dwindled.

According to state Department of Public Instruction records, the catchment area for students attending these former black high schools included students from the historic town of Bath, Belhaven, Pantego and other hamlets within eastern Beaufort County and parts of Hyde County.

In the years before the 1954 federal lawsuit Brown vs. the Board of Education, most public schools in the southern United States and the Midwest were segregated and disproportionately funded based on race, with the schools attended by children of color receiving less public funding than majority public schools. Educators and administrators working in the minority-led schools, though a part of the state’s public educational system, earned nearly half of what white educators with comparable or lesser educational preparation earned, while having to meet the same state, national and local standards for education. All students were being educated under federal rulings known as “separate, but equal.”

During those years, minority school administrators, teachers, parents and community supporters created alumni clubs for support of an annual school homecoming in which graduates of the former black high schools returned to celebrate: fundraising for scholarships for deserving minority students and to support alumni activities, while recognizing educational successes with May pole decorations, scholarship banquets, naming of high school queens and kings, and school dances and parades.

The Beaufort County High School Alumni Club of Pantego was established 57 years ago; the Belhaven High School Alumni Club, two years later. Each club created chapters in cities where large numbers of alumni resided; the largest groups were established in Brooklyn and Manhattan, New York.

Across the south and many parts of the midwest, many black high schools were closed or were transformed to middle and elementary schools following public schools’ integration, leaving the alumni groups to determine their fate. In North Carolina, some black high school alumni groups remained functional. In other eastern North Carolina towns, black high school alumni groups such as the alumni of C.M. Eppes High School in Greenville, H.B. Suggs in Farmville and Bethel Union High School in Bethel annually host school reunions and homecomings.

“The school homecomings were meaningful over the years because they represented the best of educational success for minority students, black and Indian, living in eastern and northeastern North Carolina,” said Ethel Mackey Brown, a1959 graduate of O.A. Peay School/Hyde County Training School. Brown’s father, the late Golden Mackey, was among the community supporters and activists who marched on the state capital in 1968 to save to black schools in Hyde County.

“The students and their teachers and administrators tried to retain a family-like connection because education for minorities was the key to progress in our communities and it continues even today,” Brown said.

According to “Along Freedom Road: Hyde County, North Carolina and the Fate of Black Schools in the South,” by author David S. Cecelski, in 1968, threatened closings of the black schools in Hyde County led to unrest and created fears of loss of educational heritage in the minority-dominated schools. During the late 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, white-dominated school boards throughout the South generally closed minority-led schools and often displaced their educational leaders following the Brown vs. Board of Education rulings.

In Hyde County in the 1968-69 school year, the proposed closure of two black schools and displacement of its educational leaders led minorities living in the county to contest the viewed undermining of the schools’ educational legacies and legitimacy. The fears associated with school desegregation are believed to have strengthened the now black high school alumni groups as they sought to sustain the legacy of educational successes for minority students, educators and administrators.

Beaufort County High School Alumni Club founder William Mebane is now 98 years old and a resident of Ridgewood Manor nursing home in Washington. His father was a school administrator at Beaufort County High School. Mebane recounted stories of how the school homecomings were intended to help the alumni stay connected to their former classmates, teachers, principals and school experiences and upbringing in the South, and to preserve the history of education successes for African Americans and other minorities.

A former educator, alumna and supporter of Beaufort County High School, Emma Lovick King now lives in Washington, D.C. and is now among the oldest living alumna of the former black Beaufort County High School.

“It is quite a testament of how far we have come in education, and it is great to see graduates and friends of the community,” King said.

In the 1940s and successive years, a large number of African-Americans and Native Americans moved en masse to urban cities in the northeast, including New York City, and to the west for employment and educational opportunities, though they sought to retain connections with former teachers and schoolmates. They joined high school alumni club chapters and each year, planned bus trips back to the schools for weekend homecoming celebrations.

“The homecomings have always been something to look forward to in our community,” said Renaldo “Rennie” Ambrose of Belhaven. Ambrose’s late father, Frank Ambrose, served as assistant principal at the integrated Pantego High School following public school integration in Beaufort County. “At times, there have been friendly rivalries between Pantego and Belhaven, especially in the years when the two schools’ basketball seasons were competitive.”

For 56 years, the Pantego school alumni group hosted buses of alumni from New York; the Belhaven school alumni group hosted alumni buses from New York for 53 years. Today, alumni continue to travel by other modes of transportation to the reunion.

Last weekend at the Pantego school homecoming, participants like Debra Saunderson, a 1981 graduate of integrated Pantego High School, brought her family from New York and reminisced about how exciting it was to travel from New York to Pantego on the alumni bus for more than 25 years, and expressed a desire to see the bus excursion return for the school reunion in 2018. No bus was sponsored for travel in 2017.

Valencia Walker of Upper Marlboro, Maryland, and 1978 graduate of former integrated Pantego High School said, “I support the homecoming because it represents the history of education for blacks. My grandmother was one of the early graduates of Beaufort County High School, and my mother also graduated from the high school.”

“It is historical, and the annual recognition and honoring of former graduating classes is always interesting,” she said.

“Viewing the older graduates on the parade floats is always exciting,” Walker said. “I especially like the food served … the fresh crabs and fish, etc. from the local seafood markets. It’s like a combined school and family reunion.”

Other participants like Onnie M. Spencer, a 50-year resident of Pantego, and her daughter, Rosalina “Linda” Spencer, of Durham, shared their delight in seeing the return of former students, educators and their families each year.

“Those still living here look forward to the return of all of the people and prepare over many months for the two days of feasting and celebrating,” said Onnie Spencer.

Rosalina Spencer, a 1981 graduate of the integrated Pantego High School, agreed.

“We really should not let this go away, and hopefully it can continue because I always love to come home and to see everybody — the older and the younger,” he said.

Through the years, mainstream and minority organizations and businesses in the area, and community leaders have supported the events as a part of the preservation of the history of education in eastern Beaufort County and in Hyde County. But today, a number of the celebrations are almost non-existent. Similar groups established in the county seat of Washington at the former PS. Jones High School, and in south western Beaufort County, the former Snowden High School, in Aurora, have held similar gatherings over the years, but now only small groups to gather occasionally.

As numbers of graduates, educators and administrators of all-black high schools grow older, organizers are concerned about the future of black high school alumni groups, and seek to share what their existence meant to the landscape of public education in North Carolina, and more important, the education of minority students living in rural eastern North Carolina.

“Our alumni clubs are striving to preserve this part of educational history in our part of Beaufort County. Each year we reach out to former graduates and their families, and hope to continue our annual celebrations with continued and greater support,” Heath said.

Ramona Brown is a Raleigh-Durham journalist and a former Washington Daily News reporter.

A reunion weekend

The Belhaven High School reunion begins with a scholastic achievement banquet Friday evening in the multipurpose room of the Belhaven unit of the Boys & Girls Club of the Coastal Plains, which is the former site of the black Belhaven High School.

The celebration continues Saturday morning with a parade and afternoon outdoor activities, which culminate Sunday morning at a local black church with a motivational speaker, gospel music and alumni club farewell. Among this year’s speakers is Dr. Daphne Brewington, a nursing administrator at Vidant Health, and a 1979 graduate of the former J.A. Wilkinson High School.

Cynthia M. Heath, principal organizer of the weekend celebration for more than 20 years, and a retired Beaufort County educator, said “the school homecoming events represent the preservation of the educational journey and achievements of former black student populations at the formerly black Belhaven High School, which in the late 1960s and early 1970s became the integrated Belhaven Elementary School.”

Today, former students, educators, administrators, staff and their families return to Belhaven to celebrate their past school experiences and to reconnect with class mates and to raise money for the future homecoming celebrations and for scholarships. As many as 200 to 300 former students and their families have gathered yearly for the weekend activities.

“The years have brought on changes, with some years drawing fewer participants, but the legacy of the educational experiences of former black students and graduates and the contributions of minority educators and administrators continues,” Heath said.

Former students of the past black Belhaven High School include the late recording artist, Eva Boyd “Little Eva,” who recorded the popular R&B song, “Locomotion.” Several returning graduates are now educational, medical, religious, community and business professionals and leaders living across the state and in other parts of the country.

Two of the state’s secretaries of the North Carolina Department of Administration are associated with the alumni group as their parents were former teachers and administrators in the former black high schools in Belhaven and neighboring Bath and Pantego. The current secretary for the NC Department of Administration, Andrea Machelle Baker Saunders, is daughter of retired Beaufort County educator, Bertha Green Baker, and her husband, retired Beaufort County retired basketball coach and educator, Albert Baker. Former DOA secretary, Gwen T. Swinson, is the daughter of late Beaufort County educator, Romaine Swinson, and her husband, late Greene T. (GT) Swinson, the first principal of the former black Belhaven High School.