The moral injury done

Published 4:11 pm Monday, December 18, 2017

The soldier was on patrol and moving into an Afghan village where the Taliban was suspected of having a presence. It was dusk and eerily quiet as the patrol entered the village. Out of one of the houses, a villager came rushing at the soldier, who fired his weapon and killed the villager. In the split second that often characterizes combat, actions are based on a host of training efforts and experience of past deployments. The soldier approached the body, still on edge over what might happen, and in a moment, horror nudged “edge” aside; the felled perceived attacker was a boy that couldn’t have been more than 12 years old.

That moment, and countless others experienced by American military over the last 15 years of war in Iraq, Afghanistan and now in Syria, speaks to the way we now go to war. Front lines run through a village or parts of an urban neighborhood, and the civilian population is pinched between insurgents and counterinsurgents. Often the adversary is part of the civilian population to be protected or to be engaged and influenced.

It is easy to see how the soldier’s moment leads to PTSD and can linger for years, rattling around inside his head, and in dreams, playing havoc with daily existence. However, there is also another feeling that affects the ideals of the soldier — the persistent, deep sense of guilt and shame that surrounds the killing. For a drone pilot sitting 8,000 miles away from the target, and watching the effect of missiles that take innocent lives or kill civilians as collateral damage of a grenade thrown just off the mark, guilt is part of the fabric of the veteran who once was that soldier. This moral injury and guilt often refuses to lessen its grip.

The last column introduced therapies for individuals with PTSD or other stress-related conditions to help manage depression, anger and anxiety and promote a fuller sense of healing. The community is important in providing these therapies as well as other opportunities that engage the anxiety and stress and provide long-term coping skills.

But moral injury is equally damning in its effect and offers similar and different obstacles to healing. The veteran can struggle with memories of actions and behaviors that crossed lines of what was humane and right, veering into dangerous territory of immorality and a direct contradiction to what the veteran believed in before the action was taken. Josiah Royce, a century ago, saw this struggle as one of divided loyalties, loyalty to the goodness and worth of community, signified by honor and integrity, and allegiance to winning the battle. The soldier faces that contradiction in battle; the veteran struggles with the price of that contradiction for the remainder of life.

Seeking forgiveness only partially addresses the injury. That which happened can’t be taken back. Royce offers the act of atonement as a means to help manage the guilt. Atonement to Royce is the “creative act of compensation” to the spirit of the human community that was betrayed by one of its own members, the soldier. Seeking ways to “pay it forward,” many veterans seek to help others, to continue commitment to that honor and perhaps as well to atone for the past by helping others. Healing from moral injury, like PTSD, involves a different person than the one who put the loyalty to community in harm’s way. Organizations like Team Rubicon offer veterans a pathway of healing through creative deeds such as responding to communities affected by disasters. In their journey, recovering addicts mirror a similar path, atoning for the harm they have caused by not just offering apologies, but by recommitting themselves to be a better person through acts and deeds and service to others.

The community has a stake in healing veterans, who represent a highly skilled work force and bring a diversity of experience to building stronger communities. A community committed to helping veterans must move beyond “thank you for your service” and other moments of recognition of the veteran’s experiences to a deeper understanding of how that veteran’s life has been affected. Families and loved ones know the changes and effects of service, but understanding the pervasive impact of war often slips by or is not considered by others in the community. Not all veterans experience moral injury, or even PTSD, for that matter, but many do. Communities that understand the healing process and provide opportunities for recovery through alternative therapy, activities and service, in the end such communities stand a greater chance of becoming whole once again.

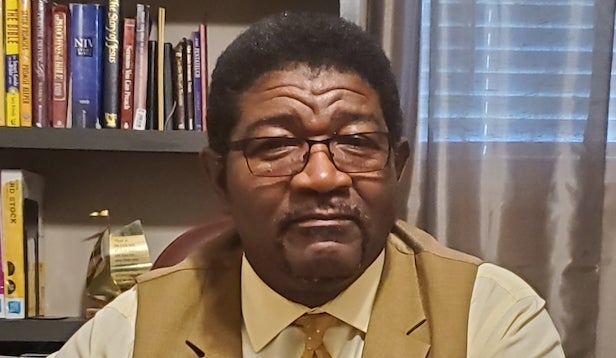

Robert Greene Sands is an anthropologist and CEO of the non-profit Pamlico Rose Institute for Sustainable Communities located in Washington.