Washington native honored for civil rights stance

Published 6:27 pm Friday, July 31, 2020

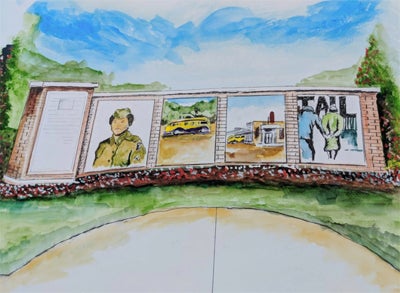

- HOMETOWN HERO: Sarah Keys Evans, pictured here in her Army dress uniform, was arrested and jailed in Roanoke Rapids on Aug. 1, 1952, after refusing to give up her seat on an interstate bus to a white passenger, three and a half years before Rosa Parks was jailed for the same offense in Montgomery, Alabama. (Sarah K. Evans Public Art Project)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ROANOKE RAPIDS — Every student of American history has heard the story of the brave African-American woman who refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white passenger, defying the laws of the time and sparking a landmark legal battle in the American Civil Rights Movement. Fewer realize that these events transpired right here in eastern North Carolina.

Sixty-eight years ago this weekend, in the city of Roanoke Rapids, Washington native Sarah Keys Evans declined to give up her seat on an interstate bus to a white Marine. Her courageous act of civil disobedience, which predated the more famous actions of civil rights icon Rosa Parks by three and a half years, will be recognized this weekend during the unveiling of a public art project in Halifax County.

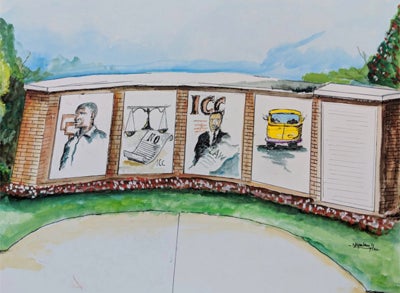

The Sarah K. Evans Inclusive Public Art Project will feature a series of eight mural panels created by Enfield painter Napoleon Hill, each depicting a portion of her civil rights journey. The memorial, entitled “Closing the Circle,” will be unveiled to the public during a ceremony Saturday morning.

“In 2017, we honored her through the Roanoke Valley Southern Leadership conference and this was an opportunity to honor her further,” said Dr. Charles McCollum, chairperson of the project. “She took a stand when it wasn’t popular, and preceded Rosa Parks, who received all of the glory for her stand in Montgomery, Alabama.”

The project is sponsored by the Eastern Carolina Christian College and Seminary, where McCollum serves as chancellor. Funding came from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, which offers grants for projects depicting contributions or achievements of North Carolinians, especially women and people of color, in parts of the state where their stories are not often told.

PUBLIC ART: Featuring eight mural panels painted by Enfield artist Napoleon Hill, along with two bronze plaques telling the story of Sarah Keys Evans, the public art installation, entitled “Closing the Circle” was unveiled to the public Saturday morning in Roanoke Rapids. (Sarah K. Evans Public Art Project)

A LASTING IMPACT

On Aug. 1, 1952, Sarah Keys Evans was traveling home to Washington from Fort Dix, New Jersey, where she was serving in the U.S. Army Women’s Army Corps. Although a 1946 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Morgan v. Virginia, had made passenger segregation illegal on buses, Evans was told upon arriving in Roanoke Rapids that she would have to move to the back of the bus to give up her seat to a white Marine.

“The driver collected the stubs of everyone that was already seated, and when he got to me, he said, ‘I want you to get up and go to the rear of the bus,’” Evans recalled in a 2019 interview by the project’s creators. “I told him I was comfortably seated where I was.”

Shortly after, Evans was arrested by the Roanoke Rapids Police Department, charged with disorderly conduct and fined $25. Released the next day, she returned to Washington, where her father encouraged her to take legal action. With assistance from the NAACP, she filed a complaint with the Interstate Commerce Commission, alleging that she had been subject to false arrest and imprisonment, based solely on her skin color.

Three years later, the ICC ruled in the case of Sarah Keys vs. Carolina Coach Company that, “The practice of the defendant requiring that Negro interstate passengers occupy space or seats in specified portions of its buses subjects such passengers to unjust discrimination, and undue and unreasonable prejudice and disadvantage, and is therefore unlawful.”

The case was settled on Nov. 7, 1955, less than a month before Parks was arrested for the same offense in Montgomery, Alabama. Today, Evans, age 91, lives in Brooklyn, New York. In an interview with Time Magazine, she says she sees the new monument going up in Roanoke Rapids not just as a tribute to her actions, but to all of “the women who have been left out” of the overall story of the civil rights movement.

“I’d like to be remembered as someone who helped somebody,” Evans said. “I like ‘pioneer’ and ‘trailblazer.’ For me, I like those terms.”

To learn more about the story of Sarah Keys Evans, and the Sarah K. Evans Public Inclusive Art Project, visit www.sarahkevansproject.com.